In 1996 Pakistan ratified the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW), declaring that it would adopt legal framework for translating CEDAW provisions not only to its domestic laws, but also to its Constitution, i.e., a reservation under Article 29, paragraph 1. However, Pakistan has yet to adopt any legal framework, which had resulted in a lack of awareness among civil society in the implementation of CEDAW.

Pakistan’s Constitution currently does not define discrimination against women, even though [some] Articles within the Constitution are of gender-based discrimination. In addition, even though advances in gender equality such as the National Plan of Action (1998), the National Policy for Advancement and Empowerment of Women (2002), and the National Commission on the Status of Women (2000) exist, they have all lacked implementing mechanisms and concrete policy measures, which have obstructed desired objectives in each initiative. Furthermore, Pakistan’s government has failed to institute policy reform in regards to “social practices sanctioning violence against women” (CEDAW Shadow Report – Pakistan, 8). That is, the Criminal Law Amendment (2004) failed to eradicate honor killings, there has yet to be a explicit law on domestic violence, and women trafficking and forced prostitution are of irrelevance.

Women Come Together to End Sexual Harassment

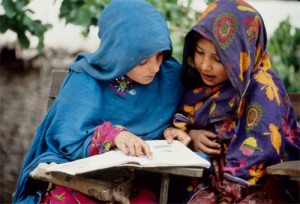

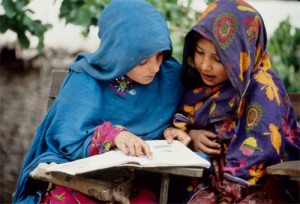

Along with violence against women, other forms of gender discrimination/inequality exist in Pakistan. That is to say, Pakistan has an extremely low female literacy rate due to a high attrition rate prior to the completion of primary school. This is the result of social norms employed in Pakistan that have consistently preferred males over females in regards to a high level of education and health, which results in widening the gender gap. In addition, even though women are active members in the national economy, they are persistently denied “adequate protective labour laws, equal wages and recognition of the value of work in economy” [sic] (CEDAW Shadow Report – Pakistan 8).

Pakistan Has One of the Lowest Female Literacy Rates in the World

In 2001 a “Health for All” policy was implemented, but government funded programs failed to improve health conditions of not only women, but also society in general. That is, “a majority of female population was anemic, malnourished, and many died every year in pregnancy due to lack of basic medical care. Paucity of health services especially in rural areas results in higher mortality rate. Lack of trained practitioners in government health units, stereotypes against family planning, added to deteriorating health conditions” [sic] (CEDAW Shadow Report – Pakistan 9).

Moreover, along with the above depictions of gender discrimination, the Muslim Family Laws Ordinance (1961) contains discriminatory stipulations in regards to marriage in Pakistan. By way of explanation, “a marriage certificate requires disclosure of the marital status of the bride only. A man can divorce a woman without proving and disclosing the reason, whereas a woman wanting a divorce has to file a suit and to go through a legal procedure for getting a divorce certificate [sic]. Rights of divorced women are not defined under any law and a woman seeking divorce has to return to the husband the bridal gifts (Mehr) which limits women’s rights to divorce. Women are not considered qualified to have the custody of children below 18 years of age after the dissolution of marriage” [sic] (CEDAW Shadow Report – Pakistan 9).

All of the above aspects of discrimination are outlined in the CEDAW Articles, in that they are important issues with regards to Pakistan itself. Although each Article is relevant and uniquely important, due to space constraints I am not able to outline the facets in each Article. Rather, I will delineate a snapshot of the importance of major Articles within CEDAW and explain why these Shadow Reports are so imperative in regards to gender inequality and discrimination, especially in Pakistan.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

The articles in Week 6 on Gender present important aspects of gender and development. Unnithan and Srivastava’s “Gender Politics, Development and Women’s Agency in Rajasthan” uses ethnographic feminist and developmentalist research in Rajasthan, India from 1984-1993 to develop an approach that is based on feminism as an epistemology. They also acknowledge the ambiguity among NGO-activists, government authorities, and academia, in defining empowerment in Rajasthan, India. Mardock’s “Neoliberalism, Gender and Development” uses ethnographic feminist and developmentalist research in Medellin, Columbia from 1998-2000 to develop a more advanced gender discourse. Both articles illustrate gender discrimination in two very different geographic areas. Still, aspects from the articles are unanimous throughout the globe and can be related to gender dialogue within Pakistan. That is, aspects such as feminism, anti-feminism, gender, empowerment, subordination, social relations, domesticity, sexual and reproductive rights, etc., can be applied to the fight for gender equality across the globe.

The United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) Women’s Studies and Gender Research Network launched [from within the Human Rights and Gender Equality Section, Social and Human Sciences Sector] a network in accordance with CEDAW to support the development of women’s studies and gender research. The gender research network is revolutionary in that, “it aims at promoting policy oriented research on and advocacy for women’s rights and gender equality, building capacities and advancing women studies, and strengthening collaboration among university/research centers on women and gender issues across continents” (UNESCO – Social and Human Sciences).

That, along with the Commission on the Status of Women amplifies the importance of CEDAW, which aims to incorporate equality of all persons within legal systems, abolish all discriminatory laws, and adopt laws that prohibit the discrimination against women. The Convention does this through Shadow Reports submitted by member states themselves on the status of women within the corresponding country. In other words, “a country becomes a State party by ratifying or acceding to the Convention and thereby accepting a legal obligation to counteract discrimination against women” (United Nations Division for the Advancement of Women – CEDAW Committee).

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Although the Articles within CEDAW vary slightly between its member states, they are fairly unanimous. Below are the Articles that are presented in Pakistan’s Shadow Report (I have highlighted the Articles in which I will focus on. I did however present each Article because they are all equally important in the advancement of gender equality in Pakistan):

Article 1, 2 Definition of Discrimination, Discriminatory Laws

Article 3 Advancement and Empowerment

Article 4 Affirmative Action

Article 5 Cultural Norms and Practices

Article 6 Trafficking and Prostitution

Article 7 Political Representation

Article 8 International Representation

Article 9 Nationality

Article 10 Education

Article 11 Employment

Article 12 Health

Article 13 Economic and Social Life

Article 14 Rural Areas

Article 15 Equality Before the Law

Article 16 Marriages and Family Relations

Article 1 & 2

There are few articles in Pakistan’s Constitution that forbid gender discrimination. In Article 26 and 27 of the Constitution it states that “there shall be no discrimination only on the ground of race, religion, caste, sex, residence or place of birth” (CEDAW Shadow Report – Pakistan 11). This is only in regards to ‘appointment in services’ and ‘access to public places’. That is, nowhere in the Constitution does it clearly state the abolishment of discrimination against women, thus leaving room for the interpretation of equality of women in Pakistan. In addition, discriminatory laws exist that encumber women’s equality.

The Shadow Reports suggests that, “the law (Constitution and other statutory laws) must define discrimination, violence against women, and acts of discrimination punishable offenses” and “in order to give de jure equality to women, repealing discriminatory laws such as Hudood Ordinance, Qisas and Diyat Ordinance, Qanoon-e-Shahadat is but imperative” [sic] (CEDAW Shadow Report – Pakistan 15).

Protest Against Hudood Ordinance

Article 3

In 1998 a National Plan of Action was adopted in correspondence to that of the Beijing commitments, to develop plans for social, economic and political empowerment. The commitments were never implemented, and were thus later abandoned by Pakistan.

In 2000 a National Commission on the Status of Women was established. Still, the Commission was given only “recommendatory” powers and lacks not only a qualified staff, but also financial resources (CEDAW Shadow Report – Pakistan 16).

In 2002 Pakistan’s government announced the formation of the National Policy of Development & Empowerment for Women for equal participation in national development. It then failed to create methods to achieve its objectives.

The Shadow Report recommends that, “the government must strengthen the mechanisms of the National Commission on the Status of Women, according to their recommendations by; an enabling mandate, independence to carry out its mandate, adequate human and financial resources and powers to investigate the redress human rights violations” (CEDAW Shadow Report – Pakistan 17).

In addition, it recommends that a National Human Rights Institution should be established to not only empower women, but also mainstream women’s rights.

Article 5

Pakistan’s government has repeatedly failed to formulate policy reform in regards to the tribal and caste system and social norms that have consistently undermined the status of women. According to the Commission of Inquiry on Status of Women, “Violence against women occurs at all levels of society and has diverse forms. It ranges from the more covered acts (e.g. abusive language, coercion in marriage) and goes on to include the explicit forms of violence (wife beating, torture, marital rape, custodial violence, honour killings burning of women, acid throwing, mutilation, incest, gang rapes, public stripping of women, trafficking and forced prostitution and sexual harassments in the street and workplace, etc.) …Many forms of it (violence) are so entrenched in our culture that they are ignored, condoned or not even recognized as violence by the larger sections of society” [sic] (CEDAW Shadow Report – Pakistan 20).

The Shadow Report recommends many ways to help eradicate violence against women. However, the suggestions are all at the state and governmental levels. Violence against women starts at home. EVERY MEMBER in the family needs to recognize that violence against persons is not right and children need to be taught that is it wrong. They only way to eradicate violence against women is to start from the bottom and work its way up, if you will.

Women Come Together to End Violence Against Women

Article 10

Pakistan has one of the lowest female literacy rates in the world according to the Asian Development Bank. This is the result of factors such as “restricted mobility, domestic engagements, early marriages, long distances to school, shortage of trained teachers, insufficient transport facilities and lack of financial resources” (CEDAW Shadow Report – Pakistan 34).

The Shadow Report suggests that a percentage of Pakistan’s GDP should be allocated towards education and that affirmative action needs to be implemented to increase the number of female children enrolled in school and female teachers in higher education.

Article 12

Health conditions of females in Pakistan are very poor. Approximately half of the female population is anemic and malnourished, which results in a heightened infant and maternal mortality rate. This is due to poor access to peripheral health facilities, poorly trained healthcare personnel, and unsafe and unhygienic conditions. In regards to reproductive rights, abortion is illegal in Pakistan (except when the pregnancy is determined by two qualified doctors to be fatal to the mother), even in the case of rape. It is thus a criminal offense under the Pakistan Penal Code.

In order to better health conditions in Pakistan, there needs to be funding from Pakistan’s GDP that is specifically for health care. That is, funding needs to be provided for training and educated healthcare personnel, creating safe medical environments for all, and giving women increased access to things needed to improve women’s health.

Article 13

In Article 34 of Pakistan’s Constitution it states that “steps shall be taken to ensure full participation of women in all spheres of national life” and Article 37 states that the state is to “promote social justice and eradicate social evils.” Article 38 states that the state is obligated to “promote social and economic well being of the people” (CEDAW Shadow Report – Pakistan 44).

The implementation of these Articles is questioned. That is, in order to execute these provisions, society must be culturally aware of gender issues and must be willing to change.

Article 16

Cultural norms in Pakistan restrict women in regards to marrying whom they choose. These norms and traditions allow for not only forced marriages to take place, but also child marriages as well.

Men and women need to be treated as equals in all legal matters in Pakistan and marriage needs to be raised to 18 years of age, according to the CEDAW Shadow Report.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Pakistan is an important country to analyze in that even though it has presented Articles/laws within the Constitution in regards to gender equality, it has persistently failed at implementing many of them. In order to end all forms of discrimination against women, society must work together at not only raising awareness of important issues that surround gender discrimination, but also work towards creating new social norms and traditions that do not involve this sort of discrimination. This will only be possible by starting at the grassroots and working up to the governmental level. That is, by educating all members of the family in each household, that will allow for consistent discourse within communities and thus within society to form. This will hopefully aid in the eventual eradication of all forms of discrimination against women. In addition, the UN, the Convention, and the Commission are all good sources on the status of women across the globe, and have all facilitated in the fight against discrimination.

Only We Can End Gender Discrimination and Violence Against Women

Sources:

“Commission on the Status of Women-Follow-up to Beijing and Beijing 5.” Welcome to the United Nations: It’s Your World. 2011. Web. 03 Oct. 2011. <http://www.un.org/wo menwatch/daw/csw/critical.htm>.

“Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination against Women.” Welcome to the United Nations: It’s Your World. 2000-2012. Web. 03 Oct. 2011. <http://www.un.org/w omenwatch/daw/cedaw/committee.htm>.

Murdock D (2003) “Neoliberalism, gender and development: institutionalizing ‘post-feminism’ in Medellin, Colombia,” Women’s Studies Quarterly, 3 & 4, 129-5.

“National Commission for Justice and Peace.” 2007. Discrimination Lingers On. CEDAW Shadow Report Pakistan. Web. 02 Oct. 2011. <http://www.iwrawap.org/resources/pdf /Pakistan%20S R% 20 (NC JP)>.

“UNESCO Women’s Studies and Gender Research Network.” UNESCO Social and Human Sciences. 1995-2011. Web. 2 Oct. 2011. <www.unesco.org>.

Unnithan M, Sriivastava K (1997) “Gender politics, development and women’s agency in Rajasthan,” in R Grillo and R Stirrat, eds., Discourses of development: Anthropological Perspectives, Oxford: Berg Publishers, 157-183.

Posted in Uncategorized